The Death Of Stalin: A Movie About The Grotesque Behind The Power Struggle For The Soviet Succession

The Death of Stalin is a 2017 political satire comedy directed by the Scottish writer of Italian origin Armando Iannucci, who took inspiration for his last movie from the graphic novel of the same name by Fabien Nury and Thierry Robin.

When Joseph Stalin, the dictator who committed countless crimes against humanity (Adrian McLoughlin), died on March 5th 1953 at the age of 74, his inner circle decided to make public his death only two days later. In that short period of time a frantic power struggle took place in Moscow to become the next Soviet leader. Stalin’s loyalists were not so well-educated and cosmopolitan than their opponents in the 1920’s, the Trotsky and Zinoviev groups, they had spent large parts of their youth in prison and exile, that is reason why conspiracy and intensive self-education have shaped their character. Most of them made their careers during the Great Terror, when one got promoted thanks to denunciation of comrades and servility to the Stalin machinery. They were its creators, rather than its products, with a record of ruthless brutalities. This blend of cruelty and awkwardness is the basis of Iannucci’s movie.

The contenders in Stalin’s succession came from different parts of the communist world. The one designated as Stalin’s ‘legitimate’ successor was the party cadre manager Georgy Malenkov, whose paternal ancestors came from Ohrid, a town previously in the Ottoman Empire, then in former Yugoslavia and now in the Republic of Macedonia. The scheming Nikita Khrushchev was born in 1894 in the village of Kalinovka, which is close to the present-day border between Russia and Ukraine. Lavrenti Beria, the sadistic secret police chief, came from the Caucasus, like Stalin himself.

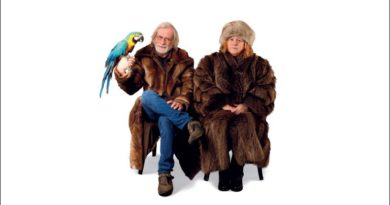

In the movie, one of the most hilarious scenes is the one where the three politicians meet at Stalin’s writing room of his dacha, where the ‘Man of Steel’ agonizes on the floor laying on his own urine. The first to arrive is Beria (Simon Russell Beale), followed by Malenkov (Jeffrey Tambor), dreadfully pale at the prospect to become the next Soviet ruler, and Khrushchev (Steve Buscemi), still wearing his pajamas under his suit. Then come the other apparatchiks, including Lazar Kaganovich, a doctrinaire Stalinist (Dermot Crowley), the Armenian Anastas Mikoyan, the U.R.S.S. greatest ice cream expert (Paul Whitehouse), and Nikolai Bulganin, another loyal Stalinist, who later will become Kruskchev’s ally (Paul Chahidi). Vyacheslav Molotov is absent from the scene (Michael Palin), because of the tense relations between him and Stalin, after the arrest in December, 1948, for ‘treason’ of his Jewish wife, Polina Zhemchuzhina.

The succession crisis turns to be worse when make their entrance Stalin’s daughter, Svetlana Alliluyeva (Andrea Riseborough), naively in love with love, Stalin’s son Vasily (Rupert Friend), a barely controllable drunk with a passion for ice hockey, and Marshal Georgy Zhukov, the glorious veteran of the Second World War (Jason Isaacs).

The movie introduces the audience to a post-Stalin ‘collective leadership’ in a comic way, describing with black humour a group portrait of the Stalin’s team without Stalin, trying to maintaining stability after his death. Stalin failed in his effort to choose a successor, when he was still alive, although designation has never been a principle of legitimacy in the Soviet system. In this analysis of the Soviet power, the Stalinskaia komanda, the leading team, finds itself suddenly leaderless, without a coach who arbitrarily decides who can play and who is to be dropped. The consequence is that, inside the team, alliances are formed and conflicts appear. After more than 25 years of Stalin-era, the cult of personality gives way to the hegemony of the apparat and Malenkov’s effort to rule through the government, independently of the Communist party, meet defeat.

The 1953 succession crisis in the Soviet Union contributed to important liberalizing changes, but did not significantly alter the totalitarian character of the Soviet regime, so Krushchev’s leadership represented rather a jeopardized bureaucratic elite’s political power, in which the real levers were still the same as before: the party machine, the secret police and the armed forces.

Strong similarities can be found between the Stalinist apparatchik system and Putin’s entourage, in a Russia where Putin will most likely still run for president in 2024, staying more than a quarter of a century in command of Russia as a stabilizer. Putin’s succession, as in the case of Stalin, creates anxiety among Russians and abroad, perhaps that is the reason why The Death of Stalin has been censored in Russia, due to its mockery of the Soviet past. Since the collapse of the socialist regime in Russia, no films have been banned and Iannucci’s film is the first ever case.